A little bit of history, today, dear readers of mine.

My family's one, actually.

But Italian history, too.

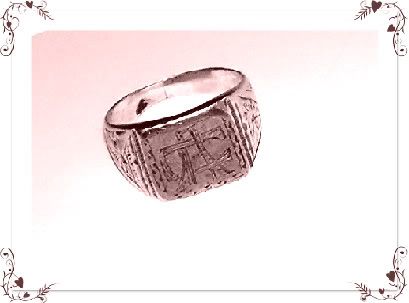

Let's start from that ring there: I wear it most of the time, wedging another ring into it to make it the right size - I have ridiculously small fingers, and it's way too big for me.

The ring in point was my grand-grandfather's, Anchise Cioni (The 'C' and 'A' in the front), who died in Greece during the WWII, lefting her wife Elena a widow and his two little daughters, Alberta (my granny) and Vanda, two orphans when they were babies, not even school-age.

Elena was sort of an unusual woman: born in the 1890s in a tiny village in North Italy (population oscillating between 50 souls when the times were florid, to a dozen when times became hard); daughter of farmers, she went to school - quite an eccentricity for a country where, at the time, 90% of people, and nearly 100% of women, were illiterate, - and learned to write and read; then she worked as a maiden for an influent family, whose members, for some funny unknown reason, used to call her "Lena".

She was no beauty, but she managed to marry Anchise, who was more than a handsome man, hiring him away from her much prettier sister; Anchise was named "The English" by friends because of his fair hair and eyes (uncommon in a country where 90% of people have a dark complexion) and tall height.

I inherited no height from him, but people say I have his hair and skin, freckles included.

Nothing is left of him (Even Elena's wedding ring, the only golden thing she'd ever had, was confiscated by the Fascist army to fund the war) except from some books, a blurry photography or two, and this ring - the only thing that won't become dust in a couple of decades.

The medal below has a more interesting story.

It was coined in Vienna in 1863, for the circa 3000 men who were part of the Brigata Estense, that is to say, the private army of Francesco V D'Este, Duke of Modena.

That name does not ring any bell?

Of course not.

It was a damn hard work to find out what the hell this "Brigata Estense" was.

Well, I finally found out that, in 1859, the Brigata Estense gave Garibaldi hell, and made the Italian Unity stagger for a while.

But, as we all know, history is written by the winner - and Garibaldi won, after all.

So, the Brigata fell into oblivion, and not many people even know it existed.

But this is its story.

June 11, 1859.

Sun has yet to rise when Francesco V, last Duke of Modena, jumps on his horse, hardly restraining emotion - a solemn departure that fits his romantic soul.

He has just been defeated by the Piedmontese army, and he has to abandon the city imediately, and for ever.

But he does not flee alone. He is the only sovereign who is followed by his army into exile.

Those soldiers follow him in Mantua for nothing else but devotion - the Duke is unable to pay them, luck is bad, and their future, more than precarious.

In addition to that, Garibaldi tries everything to convince them to come back: they're making a fool of him in front of his men, and in front of Austria. If the Duke is still in charge, the Italian Unity is in danger.

He tries to buy them, then to threaten them. But, for the following four years, those young men stay by Francesco's side.

He himself tries to convince them to go back home, not wanting them to be punished, or their families threatened.

He discharged the troops, but only 172 people, out of 3000, choose to go back. The others stay.

Meanwhile, about 1000 people come from Modena and ask to join the Brigata. The story of its courage and loyalty is spreading fastly through Italy.

But the destiny of the Brigata is doomed. In 1863 Francesco and his wife, Aldegonda - whose eyes are tear-filled, and who burst into tears before the ceremony is over - decorate every man with a medal, whose back beared a sentence.

Fidelitati et costantie in adversis.

Loyalty and constancy in adversity.

1863

And there I come into play.

About one year ago, I was ransacking my grandmother's attic looking for a mourning veil that was my grand-grandmother's, when I run into this little dusty metal disc. There and then, I though it was some old tin cork or something. When I found out it was a medal, and that old, I was sure it was some worthless modern reproduction. What a surprise when I asked an antique dealer for information, and he said that, being a fan of the Brigata story, he had been looking for a copy of it for nearly 20 years, and he offered to buy it from me!

I never found out who was the brave relative of me who followed his prince that morning of June 1859, but I have a feeling that he was Sante Cioni, my grand-grand-grand-grand-father, born in 1840, dead in 1927.

But, whoever he was, he had to be nearly my age when he left his home, his family and friends and maybe his fiancè, and everything he had, to go far and away for who knows how much time.

Once I made researches to build my family tree: I found out that four generations of people was born, and died, in the same mycroscopic village, Camatta; population: about 300 people in the 1850s (Wiki).

We, modern people, used as we are to travel here and there everytime we like to, probably don't understand what it was like, in 1859, to leave one's house for a place, Mantua, that was 70 km (44 miles) far: at the time, when everybody born and die in the same town, in the same house, and never see another place, in a whole life, it looked as distant as the moon.

But Sante, or whoever he was, left everything behind and followed his leader, on his feet, for 70 kilometers, and remained where his leader was - a foreign country, where everybody spoke German and stared at them as they were a crowd of country bumpkins - for more than four years. I wonder if anyone, now, would even think about doing something like that.

Loyalty and constancy in adversity.

1863

And there I come into play.

About one year ago, I was ransacking my grandmother's attic looking for a mourning veil that was my grand-grandmother's, when I run into this little dusty metal disc. There and then, I though it was some old tin cork or something. When I found out it was a medal, and that old, I was sure it was some worthless modern reproduction. What a surprise when I asked an antique dealer for information, and he said that, being a fan of the Brigata story, he had been looking for a copy of it for nearly 20 years, and he offered to buy it from me!

I never found out who was the brave relative of me who followed his prince that morning of June 1859, but I have a feeling that he was Sante Cioni, my grand-grand-grand-grand-father, born in 1840, dead in 1927.

But, whoever he was, he had to be nearly my age when he left his home, his family and friends and maybe his fiancè, and everything he had, to go far and away for who knows how much time.

Once I made researches to build my family tree: I found out that four generations of people was born, and died, in the same mycroscopic village, Camatta; population: about 300 people in the 1850s (Wiki).

We, modern people, used as we are to travel here and there everytime we like to, probably don't understand what it was like, in 1859, to leave one's house for a place, Mantua, that was 70 km (44 miles) far: at the time, when everybody born and die in the same town, in the same house, and never see another place, in a whole life, it looked as distant as the moon.

But Sante, or whoever he was, left everything behind and followed his leader, on his feet, for 70 kilometers, and remained where his leader was - a foreign country, where everybody spoke German and stared at them as they were a crowd of country bumpkins - for more than four years. I wonder if anyone, now, would even think about doing something like that.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento